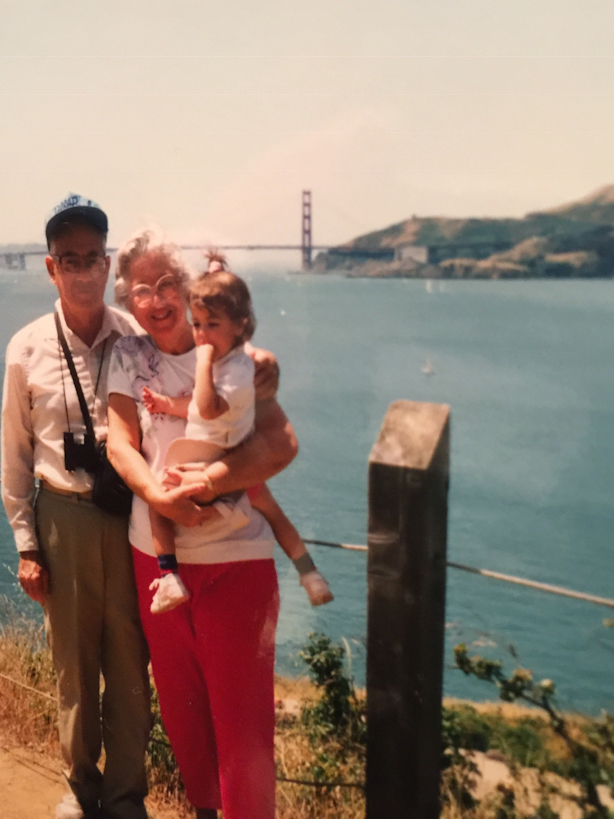

When we moved to California from Philadelphia 27 years ago, David and I made a vow: we'd ask Teddy and Willie to visit twice a year for four to six weeks. We wanted to ensure that our daughter Kaley grew up knowing her extraordinary grandparents.

They not only came... and babysat... and repaired, they also created their own California life.

After cooking a farmer-sized breakfast and doing chores, they'd take off for the day. The ferry to San Francisco to tour museums and shop produce in Chinatown...or a picnic lunch by the Pacific Ocean. Then home for a delicious dinner cooked by Teddy and bed by 10pm after their ritual, a nightly bowl of cereal.

Sometimes I'd tell friends that we'd run out of repair jobs. The reply? "Send them to us!" They'd all adopted Teddy and Will as their own.

Step into our house when Teddy and Will were visiting and you'd feel the same rhythm that defined their home.

Steady... slow... re-assuring. They wrapped us all in a secure blanket of love that lives on.

Willie is the master cabinetmaker, the quiet intellectual. His hand-made 18th century creations now dot the home of Diamonds across the nation like the canopy of a deeply rooted oak.

In each masterpiece, we feel his hands smoothing... and carving.. and polishing.

Teddy is smells wafting from the kitchen, the sound of pots and pans. Ground zero of all Bubbiness where she whipped up the delicacy that celebrated every Diamond child ...the Knish.

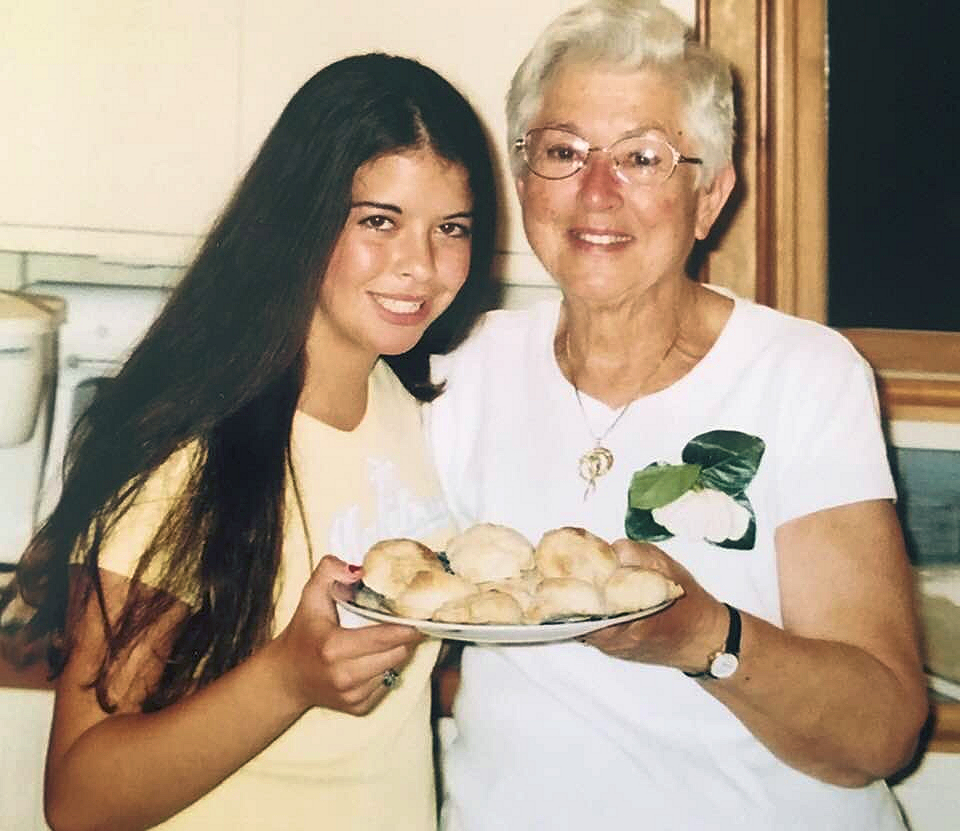

Not heavy-as-a-rock, aches-in-your stomach knishes. But knishes so light and flavorful that they'd be honored guests among the flakiest of Danish pastries.

For these are Bubby's knishes, rolled and spun from her hands. In her knishes is all that's rich and kind and delightful about Bubby herself. You could say that eating Bubby's dainty knishes is like absorbing a bit of Bubby.

For every baby naming and bris... every bat or bar mitzvah... wedding and anniversary, Bubby's children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were honored with the gift of the knish.

Preparations began weeks in advance. And if they were traveling knishes, Bubby called ahead with military precision to ensure that there were enough plastic containers to hold 400 knishes. And enough freezers in the neighborhood to preserve them. Until it was time to layer them on platters, heat them in the oven and finally present them to guests.

She knew that at every step, a knish could go wrong-a soggy or unflakey aberration that would not live up to expectations.

Once tasted, people were smitten be it the delicate ground beef version, fluffy rice or savory potato.

At our daughter's bat mitzvah guests blocked the entrance from the kitchen like linebackers ready to assault caterers bearing trays of the treat.

We lived 3,000 miles from Bubby's home base, Philadelphia, but years after first encountering a Bubby knish, people still asked: Is Bubby visiting soon? And might she be making knishes?

When Bubby turned 80, fear struck the Diamond clan. She started talking heresy-- retiring the knish. Turning out hundreds for every family rite of passage was weighing on her. Even after training Willie in the art of prepping a mountain of potatoes, onions and parsley, she was wearing down.

For the art of the knish lies in making and rolling out the dough. Instead of having the thickness and consistency of a flat tire, Bubby's dough was paper-thin, more like filo dough used for baklava, so difficult to create that machines roll out each sheet.

Fortunately, instead of retiring, she continued cranking out knishes. For Bubby, knishes were like a thread that knit together generations of her descendents.

On the morning of knish making, everyone steered clear of the kitchen. Bubby rose at dawn to sniff out the variables that tamper with success-too humid or too dry makes the dough temperamental or too brittle. Based on her tests, she'd adjust the recipe and by 8am, the kitchen was humming.

Willie, a man who didn't know how to boil water until he was 65, alternately peeled potatoes, diced onions and browned ground beef.

Bubby realized one day that if she went first, her soul mate of a husband wouldn't know how to cook for himself. So she taught him, transforming Willie into a masterful sous chef.

When the dough rolling and knish wrapping started, no one interfered. Interrupting the rhythm would be like disrupting Fred Astaire, mid soft-shoe. It wasn't until late afternoon that bite-size, golden-brown knishes covered the counter tops. The aroma wafted outside and we'd find a steady stream of neighbors at the door, asking: Is Bubby baking up a new batch?

At 87, Bubby flew west, this time for her grandson's June wedding in Los Angeles. Would there be knishes? The answer was uncertain.

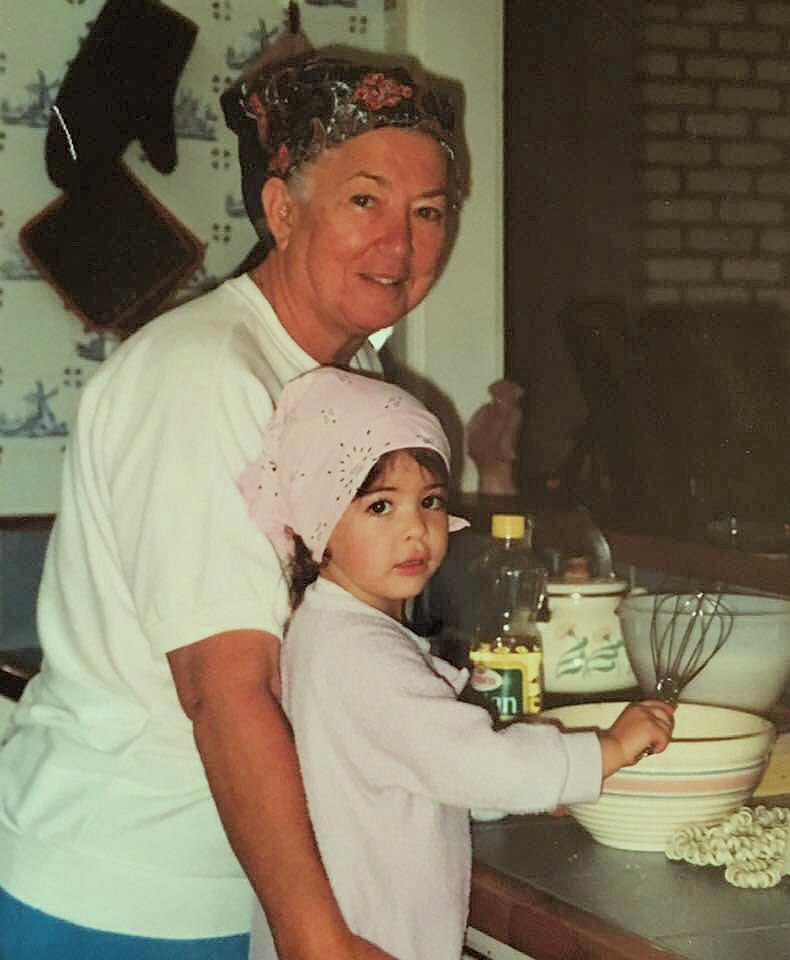

The Diamond clan had already taken steps to ensure the immortality of the Bubby knish. Click on mymishpacha.com and voila! You'll see Bubby... her hair carefully wrapped in her signature kerchief offering a step-by step tutorial on the art of knish making.

That June she came first to our home for knish making. Instead of a solo production, this was a team effort, an insurance policy of sorts. Kerchiefed Bubby in command at the kitchen table made by Willie showing her son and daughter-in-law and granddaughter how to roll, fill and assemble magical Diamond knishes.

It's been almost three decades since we moved west. Everywhere you turn in our home, you'll find Teddy and Willie. The curly maple chests by our bed, the grandfather clock, the handmade bed for Kaley, Teddy's recipes. Photos on the walls include Bubby and her two-year-old granddaughter cooking together in matching kerchiefs. Even in cyberspace. Kaley's cooking blog is named wannabebubbie.com.

Teddy embodies what I hope to be. In her ninth decade, she so deftly navigated the world that few realized she had just five percent vision and was deaf without hearing aids. If at 96 I'm listening to books on tape that range from all 832 pages of Hamilton to Bruce Springsteen's autobiography and debating the nightly news, it means I will have achieved another of Teddy's accomplishments. Remaining open and curious and vibrant to the end of her life.